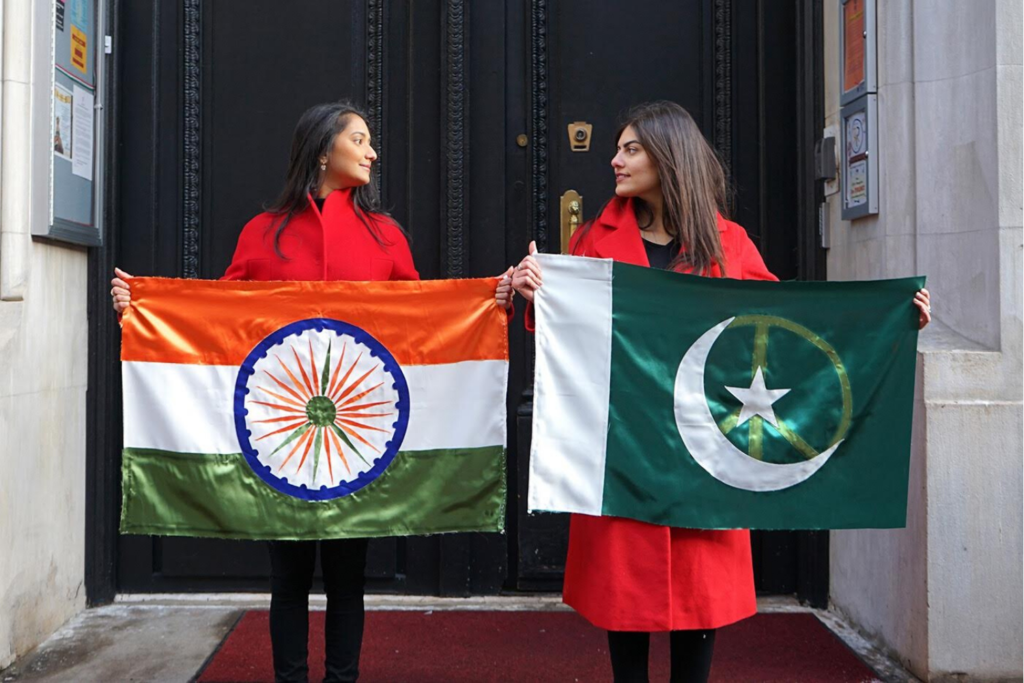

Cover photo credit: Ushah Kazi

Op-ed writer: Ushah Kazi

Pakistan’s IT sector has been a rare ray of hope amidst the economic uncertainty that the country has grappled with for several years. This year alone, while most of the economic prowess and potential seemed to have been curbed if not completely stifled, the IT industry continued to grow, and even prosper.

Reportedly achieving a 62% year-on-year growth, with IT-related exports recording a 21% increase in ten months of the current fiscal year as compared to the last, by April 2024 it had amassed $310 million in inflows.

Thus, it should not perhaps come as a surprise that when Pakistan’s budget for 2024-2025 was released, there was a noticeable focus on the IT industry, with a proposed ‘development budget’ being set aside for the IT and telecom sectors.

But upon closer inspection; there are some key details about the current budget and its approach towards Pakistan’s promising but also nascent IT sector, that may be a cause for concern.

Having The Cake…

From the onset, an aspect of the 2024-2025 budget that economists and scholars had been apprehensive about was its penchant for government spending. Writing for PRISM, economist Uzair Younus highlighted that at Rs. 24, 388 billion, the current budget’s total expenditure has seen a 77% increase from its 2022-2023 predecessor.

Elucidating the problem with this approach, Sakib Sherani, who has served on several economic advisory councils in the past, noted that “on the expenditure side the federal budget’s absence of a reform vision and intent is woefully apparent”.

The concern raised by experts is that increased government expenditures not only add to the overall public debt (something that Pakistan’s current economic realities cannot sustain) but also do not enable the structural changes necessary for the economy to benefit in the long run.

And when it comes to the country’s digital economy, a similar pattern emerges.

While the govt has allocated significant sums towards the development of the IT sector, the nature of the proposed projects has raised alarm bells. According to Profit, while the budget proposed more than Rs. 79 billion investment in the IT sector, much of the focus is on ‘IT Parks’ including “Rs. 8 billion for an IT Park in Karachi and Rs. 11 billion for the development of a technology park in Islamabad…”.

Weighing in on the situation, economist Maha Rehman, while commending the focus on digitization, noted that such ventures will not have the required benefits for the industry’s productivity. As she explained it, “we need to build the right human capital and solid countrywide infrastructure that will propel this forward”.

In fact, prominent stakeholders have gone further and warned about the budget’s ultimate impact on the industry. Ali Ihsan, senior vice chairman of the Pakistan Software Houses Association (P@SHA), likened the budget to signing a “death warrant” for the IT sector.

P@SHA had reportedly conveyed many of the industry’s requirements and grievances to relevant government bodies. Earlier this year, the organization had even unveiled an ambitious set of budget recommendations that included targeted tax exemptions and policy changes, that would have reportedly helped the industry expand on its growth potential.

However, the final budget has left representatives from P@SHA apprehensive, to say the least. Muhammad Zohaib Khan, the chairman of P@SHA, lamented the government’s allocation of expenditure towards its own projects, as opposed to making allowances that would help the IT industry itself.

An Ever Widening Net…

As mentioned, P@SHA had earlier this year published its own set of budgetary recommendations. Not only did they provide a snapshot of what industry stakeholders had envisioned, but they also shed light on some of the hurdles that are currently curbing its potential.

For example, a notable tax exemption that their recommendations requested was regarding the taxes levied on salaried persons employed by the IT industry. Their report noted that like all salaried workers in Pakistan, income tax was deducted from IT workers’ salaries. In contrast, people in Pakistan working remotely for foreign IT firms “are taxed under section 154A at a much lower rate…”

This, their report suggested, made it difficult for local firms to compete with international employers. Altering this taxation setup would make it easier for local firms to hire top talent.

The report also encouraged tax exemptions that would further help IT and IT-enabled services (ITeS) export their products and services. This would benefit the Pakistani economy overall, and capitalize on Pakistan’s digital potential as well.

However, the 2024-2025 budget seems to have pivoted in the opposite direction. The ambitious spending plans outlined in it, are predicated on an increase in revenue by way of tax collections. That is, we will see an increase in government spending (primarily to create more government employment) afforded via further taxing an already burdened citizenry, as the measures outlined are mostly directed towards people who are already reeling under inflation and instability. Sakib Sherani elaborated that “new tax measures equalling 1.8pc of GDP, mostly coming from existing taxpayers, are expected to propel the targeted increase in tax revenue.’

Uzair Younus called the measures “outrageous” noting that “the government seems to continue extracting money from ordinary citizens to pad the wallets of those who work for the state”.

And despite its potential, Pakistan’s IT sector will not be immune to these changes. Noting how the measures contradict what industry stakeholders had asked for, Muhammad Zohaib Khan said higher income taxes on the salaried class included in the budget would “further fuel the brain drain of the skilled workforce from the IT industry of Pakistan”.

Simultaneously, he lamented that instead of “removing the anomalies of current tax laws” the budget has expanded them as “additional taxes have been levied on imports of equipment and GST on hardware has been counterproductively enhanced from 5 percent to 10 percent”.

Lost Potential?

Pakistan’s IT industry has pushed ahead, often despite the challenges that the country as a whole faces. According to experts, not only does it offer a lucrative career path for local talent, but it can also serve to alleviate many of the downturns that Pakistan’s economic growth faces. In April 2024 alone, IT exports from Pakistan had grown by 62.3% as compared to the year before.

But as has been the reality for the country itself; nothing can curb its potential quite like misguided policy. Whether this year’s lackluster budget has done the same for Pakistan’s digital future, remains to be seen.

Ushah Kazi has written for a number of Pakistani and Canadian publications. She has also published a book about Pakistani cinema titled, The Pop-Culture Junkie’s Guide to Pakistani Cinema, which is available on Amazon.