Cover photo credit: Ushah Kazi

By: Ushah Kazi

Pakistan, like many other countries in the region, has a turbulent, colonial history that it continues to grapple with. Particularly as the digital age allows more and more Pakistanis to voice their agitations regarding the vestiges of British colonization.

The monarchy, for example, is often scrutinized for its history, and continued influence. While the recent death of Queen Elizabeth II was met with sadness across South Asia, scholars and historians also took the opportunity to critique her role in the politics of the region. They raised questions not just about the history of colonization and how that continued to impact countries such as India and Pakistan, but also the queen’s insistence on ‘non interference’ when she could have played an important role in mitigating conflicts.

And yet, Princess Diana is a rare royal, who avoids most of that scrutiny. In fact, many would argue that the late “People’s Princess” was and continues to be a popular figure in many South Asian countries, Pakistan included.

Consider this, here’s an image that I took on the streets of Hyderabad, in 2021. Nearly 24 years after her death. Not just is this beauty salon using her image, but the name ‘Diana’ itself.

A lot can be said about Pakistan’s “colonial hangover” and how our history permeates via accepted beauty standards and celebrity culture. Still, it is worth exploring why Princess Diana is singled out in the way that she is.

For example, in an article titled ‘An Ode To Princess Diana’s Special Relationship With Pakistan’, Saman Shad starts the piece off by stating, “if you ever mention Princess Diana to my mother she will look back at you misty-eyed. “She was so wonderful,” she would say, followed quickly by, “gone too soon…”

Colonial hangover and beauty standards notwithstanding, not every British monarch or foreign celebrity elicits such reactions. Why then, is Diana an exception? Her multifaceted relationship with Pakistan offers up some explanations.

The people’s princess; Diana’s links to charity

The late Princess of Wales visited Pakistan thrice. First in 1991, then in 1996, and finally in 1997 a few months before her death. Her first visit to Pakistan was significant not just for the country, but for Diana herself. It was her first solo trip as a royal, and as noted by People Magazine senior editor Michelle Tauber, she used the trip to put a lot of emphasis on causes that mattered to her.

By the time she came back to Pakistan in 1996, for a fundraising event for Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital, Princess Diana had already been working to raise awareness about, and funds for cancer research elsewhere. In 1993, she opened the Wolfson Children’s Cancer Unit at the Royal Marsden Hospital in Surrey, and in 1996 helped raise more than $1 million to support cancer research at the Lurie Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

When she visited Lahore in 1996, there was a lot of speculation about the trip. News reports from the time reveal that Imran Khan was criticized for using the trip to bolster support for himself in a bid to enter politics. In hindsight, however, the trip and the princess herself are often remembered favorably by many in Pakistan in lieu of her charitable work.

She visited Pakistan again the following year and was again instrumental in raising funds for Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital. Interestingly, this was after her divorce had been finalized. It was another instance of Diana engaging with people; sans the monarchy.

A few weeks after her final visit to Pakistan, the Princess of Wales died in an infamous car crash. Imran Khan (chairman of Shaukat Khanum Memorial Trust, who would go on to become Prime Minister of Pakistan), revealed in an interview that she had made the 1997 trip at his behest, adding that she had arrived on short notice. While reacting to the news of her demise, Khan called her “a friend in need,”

While her visits to Pakistan took place many years ago, they continue to endure. For instance, when the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge made their own trip to Pakistan in 2019, parallels were drawn between Kate Middleton and the late princess.

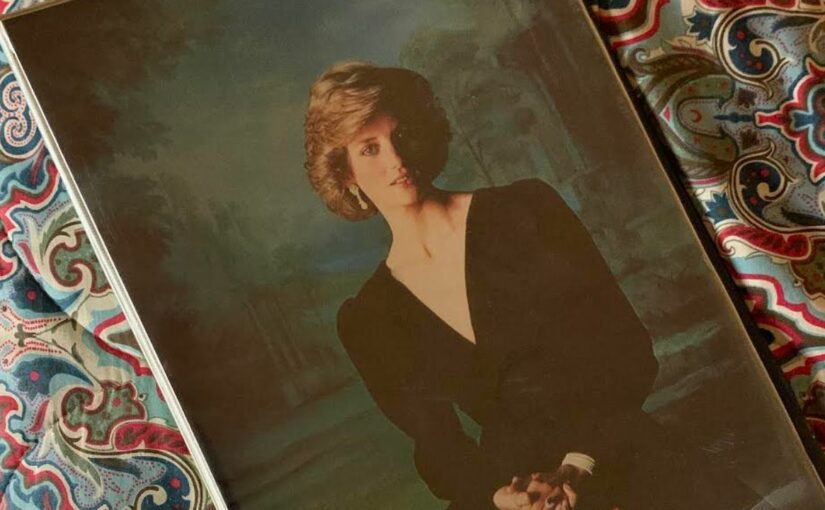

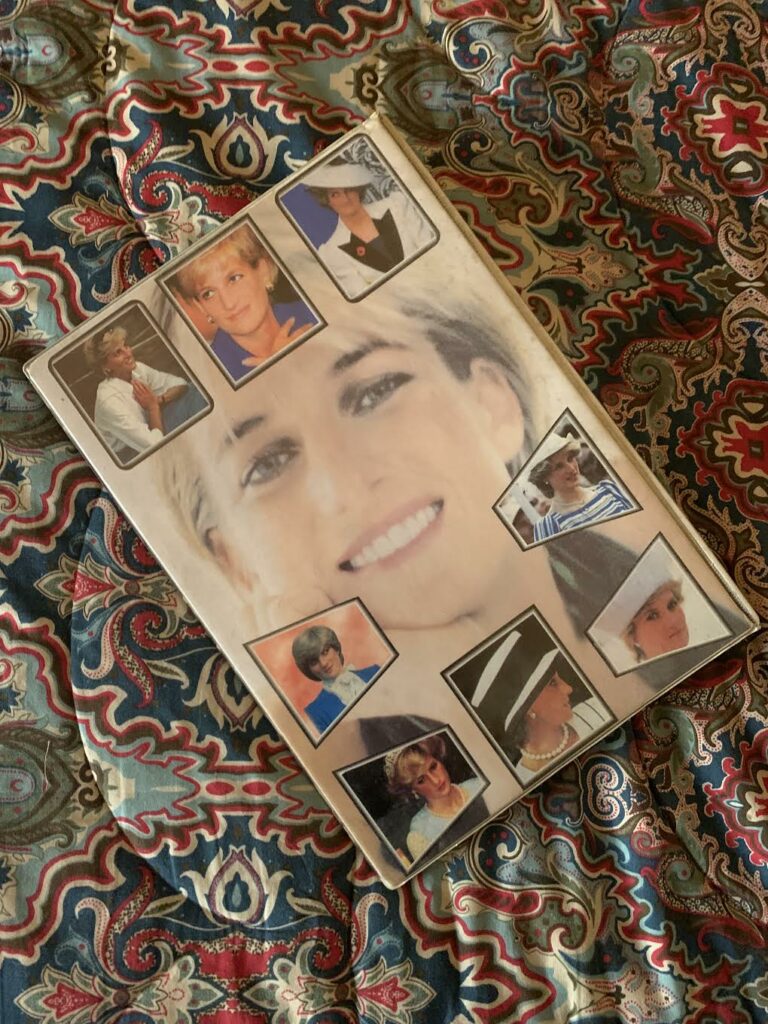

An iconic image

During her life and posthumously, Diana is recognized as an iconic figure. Always popular for her beauty and style of dress, she was at a time one of the most photographed women in the world. Her position in global iconography would play an important role in bolstering her appeal to the public.

As pointed out by Eleri Lynn, Curator of the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection, in a Vanity Fair article, the late royal’s style was curated in a bid to communicate. “It is very surprising how little footage there exists of the Princess actually speaking,” she said, “we all have a sense of what we think she was like, and yet so much of it comes from still photographs, and a large part of that [idea] is communicated through the different clothes that she wore.”

Veteran Pakistani fashion designer Rizwan Beyg (who designed one for her more than once) maintained that how Diana presented herself when she visited Pakistan also made a statement.

In a recent interview with Samaa, he described her style as “experimental” in that, “she was one of the few people who had broken away from the typical monarchy, of what they used to wear.” He noted particularly that her travels often reflected in the clothing she wore.

In light of her penchant for standing out, Beyg, who was asked to design for her by her friend Jemima Goldsmith, settled on a “more feminine” version of an Achkan, which is traditionally worn by men in Pakistan.

As noted by Lynn, the clothing that she wore conveyed messages, even when she didn’t speak. In relation to Pakistan then, what she wore has singled her out as an elegant figure from the pages of history. Her ensemble is routinely lauded by local publications (even after all these years). And even in Diana-focused memorabilia that can be found in Pakistan, the iconography follows the same narrative.

Media scrutiny: Dr. Hasnat Khan and The Crown

It would be fair to say that ‘Diana Mania’ has entered the digital age because of the popular Netflix series, The Crown. Albeit the show itself has elicited mixed responses. In particular, the historical revisionism that the series is accused of has often invited controversy. For example, Jemima Goldsmith, who had been brought on to help write the script for the fifth season, felt that the series did not depict the late princess “as respectfully or compassionately” as she had hoped. She went on to cut ties with the series as a result.

The latest iteration of the show deals with arguably the most turbulent yet well-known time period pertaining to the British monarchy (the 90s). This coincidentally was also the time when Princess Diana was most actively seen in public. But, the show shortens or skims past much of her life, work, and even personhood.

In a scathing review of the fifth season for Vulture, critic Roxana Hadadi derided the series for its portrayal of the princess. Writing, “gone is the Princess Di I remember: the woman whom my Iranian mother and other female relatives spoke about with warmth and empathy and whose kindness, interest in other cultures and countries, and desire to take control of her own life …made her a beloved figure in diaspora communities around the world.”

Hadadi contends that the show presents her as a “vengeful, immature and materialistic” person who is “easily distracted by clothes and men.” This treatment arguably extends to how her tryst with Pakistani-born cardiologist, Dr. Hasnat Khan (played by Humayun Saeed) is presented. Relegated to two episodes, their relationship is portrayed as a fleeting encounter. In reality, however, it didn’t just last longer but was also a lot more complicated. As revealed by Jemima Goldsmith in a 2013 interview with Vanity Fair, at one point the relationship was allegedly so serious that Diana was considering moving to Pakistan.

Dr. Khan, who is famously private, has said that he was “good friends” with the late princess.

Diana in the public eye

On a rare occasion, when Dr. Khan did speak to the press in 2021, he was particularly vocal about the media scrutiny she was met with. Commenting on her explosive 1995 Panorama interview with former BBC journalist, Martin Bashir, Dr. Khan claimed that Bashir “exploited” the late princess’ “vulnerabilities”.

Dr. Khan spoke of the incident after Princess Diana’s brother, Charles Spencer, had alleged that Bashir used forged bank documents and false information to get her to agree to the interview.

Since then, the BBC has had to donate the amount it made from the interview and compensate Diana’s former private secretary for damages.

There are mixed reports about what the late princess herself felt about it. According to Dr. Khan, a young Prince William allegedly told her that she had made a “mistake” and referring to Bashir said, “mummy, he’s not a good person.” However, her biographer Tina Brown maintained that Diana did not “regret” the interview.

What we can be sure about, however, is that the candor with which she spoke about her mental health, struggle with an eating disorder, and marital problems made her even more popular. Apart from, arguably, the most famous Diana quip of all time (“there were three of us in the marriage, so it was a bit crowded”) she also detailed how Prince Charles was jealous of the attention she was garnering.

In hindsight, this acknowledgment of the cracks in her marriage made her appeal even stronger. As NPR producer Mia Venkat highlighted, perhaps what allowed women from diverse backgrounds to relate to Diana more than anything else was that she too struggled in a loveless marriage. Moreover, South Asian women could relate to the pressure of staying in such a union because of the taboo surrounding divorce.

Simultaneously though, the fact that she did go on with the divorce, and continued to work in spite of formally separating from the monarchy, only added to her legacy.

As Hadadi highlighted in her article, it was the late princess’ “willingness to break away from the monarchy’s façade of happiness and steadiness,” where she was able to “go rogue with her charity work” and express her emotions, that cemented who she was, and how she would be remembered.

Perhaps those same moments of international renown, that betrayed her spark and independence, have also captivated Pakistan for all these years. Moments that set her apart as the most dazzling royal and royal dissenter almost simultaneously. Where many British monarchs would make the trip to Shaukat Khanum, Diana would be held up as the benchmark. Where foreign dignitaries would try their hand at embracing local fashion, no one would be quite as elegant as the Princess of Wales. Where other royal rebels would form a bond with women across the country, nobody would be met with as warm a reception as the late Lady Di.

Ushah Kazi has written for a number of Pakistani and Canadian publications. She has also published a book about Pakistani cinema titled, The Pop-Culture Junkie’s Guide to Pakistani Cinema, which is available on Amazon.